Material For Spreader Bars – What Should I Stock?

So you are setting up to build spreader bars and you are wondering if you should stock material and what types of material to stock before you start? This is a pretty common problem. Many people, especially when they start, don’t have a full-scale fabrication shop running and don’t necessarily have a need or the capital for a well-stocked steel supply. The good thing is for spreader bars you won’t need very many grades of steel; the bad thing you will need a number of different sizes.

Material Grades:

When you are selecting which grade of material to stock, it’s probably a good idea to start with reviewing what the engineer has specified. They should be specifying a material with around 50,000lb yield which can come in a variety of specs across the world. For tubing, I commonly specify a 50W (CSA G40.21) or ASTM A500 grade C because that is the most common structural steel. Both 50W and A500 are low carbon steel that have high weldability and a good track record for being a great material option. If you are operating outside of North America or are unsure about that materials, most good steel supply companies can help you find an equivalent steel as those listed above. Everyone in the steel supply industry should all be very familiar with those selections and able to help you. For plate steel, I generally use a 44w or equivalent grade but I stay away from the more common ASTM A36 because of the MTR issue. A personal favorite material of mine is quenched and tempered high tensile steel. I love designing with this material because it has a high strength to weight ratio and excellent material properties.

MTR

This brings me to the second important part when selecting and stocking materials, the MTR. The MTR can be called Material Test Record, Mill Test Report (or any number of variations) and is a document that is produced when a sample of that mill run (of material) gets tested or undergoes its quality control process. The quality control process and the tests done are governed by the standards the producer is trying to achieve. For instance, 44w has a different standard than A36 and each code specifies different required properties. If it meets that requirement, the material is officially that grade.

You can find and buy these standards such as http://www.astm.org/

Spreader bars are a structural piece of equipment that people rely on to keep them safe and therefore you should only utilize material that has some sort of documented quality control process and meets a known grade of material.

So back to why not A36? It is important when dealing with structural components that the MTR includes yield testing, elongation and performance at lower temperatures (especially important for Canada). This is not part of the ASTM A36 code but is part of the 44w or A500 codes. Now that I said that, it is common with A36 for the supplier to exceed the code and still do material testing but isn’t always the case so check to be sure.

MTRs also help prove traceability on your material which is an important feature if something ever went wrong and you needed to prove which material was used. So when you buy materials make sure there is an MTR and it is a good practice to have someone review the MTRs to make sure what you are getting is the same as what the engineer specified. At minimum you want to review yield strength but depending on what you are doing you might need a more thorough review. You should also keep your MTRs for several years after the project leaves.

Sizes:

The complex question is what sizes to stock. To make things easier I personally try and stay away from designing with I-beams. This is because there are so many versions and sizes that obtaining supply and stocking material can be very difficult. You also can’t do telescopic versions of anything with an I-beam so I will focus more on the tubing or hollow structural steel (HSS). When discussing HSS you need to consider the parameters of available lengths that come from the mill and which thickness you need for the design.

Lengths:

Most material will come in lengths of 20’ – 50’ and specific intervals such as 20’, 24’, 25’, 30’, and occasionally on some weird intervals such as 48’. But it changes from material to material and what your supplier has access to. When building spreader bars, you will inevitably need access to a wide array of tubing sizes and usually on short notice so it is important to develop a good relationship with your steel suppliers as soon as possible. All the different lengths also mean material utilization can be an issue. It always seems to happen that you land a great sale for 60ft long telescopic 50ton spreader bar and realize you need two 30ft lengths (approximately) to make each section but can only buy the material in 48 ft lengths. Which leaves you with 18ft of waste. All I can say is try your best to produce as few short sections of material as possible. If there are short sections you might consider making a smaller length beam for stock. I would recommend that you do a little exploration about buying material cut-to-size vs buying full lengths and trying to figure out what to do with the excess. Steel supply companies will always charge you a handling fee for cutting material to length but occasionally because they move a lot of material they could have a use for the offcut and it might end up being cheaper than putting it in inventory.

Thickness:

The strategy with thickness is balancing material sizes that will fit in each other for use with the telescopic spreader bars without requiring stock in every size. I use a couple rules of thumbs to make this easier.

- Pick a minimum size. For me, I don’t use material smaller than 2.5” tubing. This means on some of the small and light spreader bars the customer is paying for more material than is actually required but I also feel the longevity of using really small materials is jeopardized. This will simplify the number of sizes you need to stock and customers are rarely unhappy with getting a larger bar as long as your costs are reasonable.

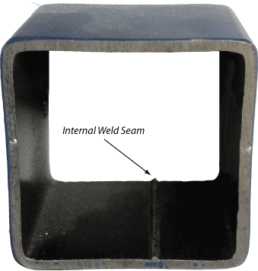

- Understand clearances. Hollow structural shapes (HSS) is generally rolled and welded at the factory into the square shape so there is a weld seam that runs down the inside of the tube. One lesson everyone learns in this industry is that paint + weld seam requires a lot of clearance. I borrowed this perfect picture of a weld seam from omega-bg.com

- Asses how often you are going to be producing high tonnage, long spread bars. 100 ton 60ft telescopic bars require some big material, but usually represent the smallest volume of sales. Do you really need to stock this material?

- Review and balance whether the risk of losing the sale because of lead time on the material makes it worth stocking at all. If you have a good supply of steel and customers that aren’t too demanding, I recommend not stocking material. Having said that, my experience is that most customers value a quick delivery more than price so this may be difficult if you end up losing days or weeks waiting for material.

- Use fewer material sizes. You can manipulate the design a bit in order to use fewer material sizes such as running two pins to get more pin surface area rather than increasing thickness.

When building telescopic spreader bars, increments of ½” with a 3/16” outside tube wall thickness work really well together for sliding. For instance, a 3x3x3/16” outside tube paired with a 2.5”x2.5” inside tube, slide really well once they are painted. Of course, the thickness of the inside tube will depend on the capacity and there is a limit to what the 3/16” outer tube can withstand before running into localized buckling issues. There are a few additional tricks and ways to handle clearances and sliding but I can probably write a full article on that so I will save that for another day.

I hope that gets you started in narrowing down which material to start stocking. Or even help you to decide if stocking material is the right move at all. If any of the terminology in this article was confusing check out the article: Anatomy of a spreader bar to learn more. If you enjoyed this article I recommend signing up for our newsletter (look to the right) so that you get notified when the next article comes out.

[…] Stocking Spreader Bar Materials […]

[…] Stocking Spreader Bar Materials […]